Hercule Poirot: Learning To Use Gray Cells

When we think of detective and crime novels, we often associate it with the novel, mainly British, from the early twentieth century. Inevitably its protagonists come to mind, picturesque detectives like Sherlock Holmes or Hercule Poirot. And precisely the little Belgian man is the core of this article.

Agatha Christie was in charge of bringing this unique character to life. Hercule Poirot made his first appearance in the novel The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920); From this moment on, she would become one of the writer’s most recurring characters, starring in 33 novels and some 50 short stories.

The crime queen maintained a love-hate relationship with her character, about him, she even said: “Why? Why did I have to bring this obnoxious, bombastic and tedious little creature to life? However, I confess that Hercule Poirot has won. Now I feel a certain affection that, even if it costs me, I cannot deny ”.

Christie’s fame grew like wildfire and, at the same time, so did characters like Poirot or Miss Marple. Some of her books have been classified as the best of their kind and her work has been translated into more than 100 languages, making her the most translated author in the world. Sales place it only below authors such as Shakespeare and works such as The Bible or Don Quixote .

Success among the public is not always linked to the adoration of the critics, for this reason, for many, Christie’s work should not be classified as literature, but as subliterature or paraliterature; in other words, a literature designed for the mass public. There is no doubt that she is an easily identifiable author and, in particular, this is thanks to Hercule Poirot.

Discovering Hercule Poirot

Conan Doyle, father of Sherlock Holmes, was one of Christie’s favorite authors. In his early novels, we identify a Poirot who follows the tradition of Doyle’s Sherlock and EA Poe’s Auguste Dupin. But over time, Christie managed to give her character an identity of her own, distancing herself from her influences and disengaging herself from the Doyle tradition.

It would not be fair to compare Poirot with other detectives of the genre or try to fit his shadow into Holmes’s profile; but, on the contrary, it deserves a separate analysis. Poirot is a character easily recognizable by the general public, he has a large number of distinctive features that make him unique and make him an exceptional and peculiar detective; detestable and adorable in equal measure.

Vanity, perfectionist, methodical, extremely organized, lover of square shapes and symmetry, a maniac who borders on pedantry and, above all, Belgian, very Belgian; thus we could describe Hercule Poirot. Christie granted Tintin citizenship to her detective as a result of his contact with Belgian refugees during the First World War.

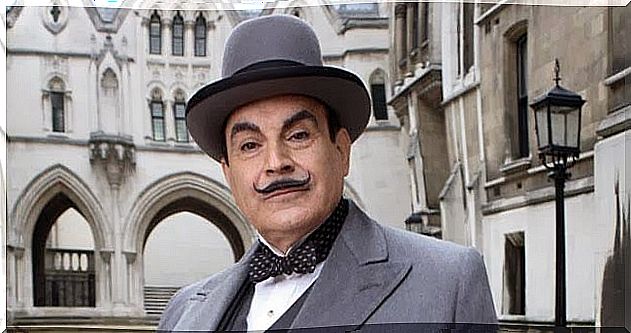

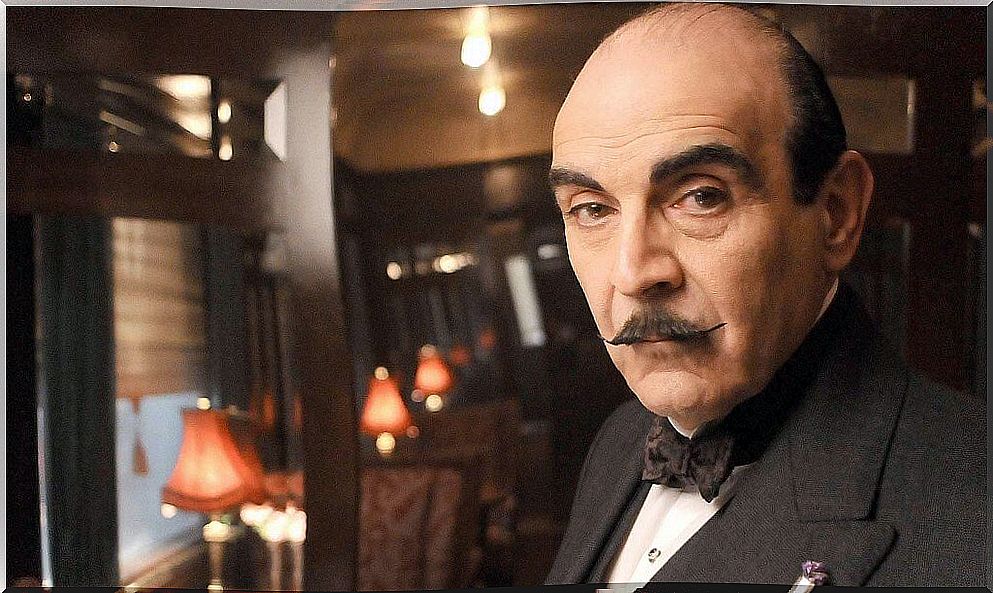

That perfectionism that characterizes Poirot is reflected in his physical appearance. Hercule Poirot is described as: short, plump, with a peculiar pointed mustache. His mustache is so perfect and cared for that it is comical; everything about him is perfectly calculated, even a speck of dust on his clothing would manage to disturb him, and there is nothing that bothers Poirot more than a slightly crooked painting.

Endless manias and extravagances will take Poirot into truly comical situations, which alleviate the tragic and macabre framework through which the character moves. This idea of the laughable in Poirot breaks, somehow, with the cliché of the burlesque fool; he moves away from the clumsy and good-natured man who produces laughter, like Sancho Panza. Poirot is an extremely intelligent detective, capable of unmasking the most heinous of murderers only with the observation and help of his “little gray cells”. Nobody manages to escape from Poirot, a detective capable of delving into the psychology of the criminal.

Poirot and crime

His obsession with perfection leads to the search for it in any situation, even at the crime scene. Christie’s works all follow the same structure: character presentation, crime, investigation and resolution. The characters tend to be high-class, the spaces are tight, and the crimes motivated by passion or money. Poirot solves crimes without getting dirty, maintaining order and calm, observing and interrogating, using psychology and reason.

In this way, he immerses himself in the minds of criminals, connects with the reader and with psychology. Christie proposes us a game: she has left all the pieces scattered throughout the book and we, like Poirot, must organize them so that everything makes sense. And that’s how Christie managed to conjugate the keys of “what you like” or “what you sell”; He knew how to connect with the public, but not so much with the critics.

Hercule Poirot in the movies

This type of work, with a simple structure and an attractive theme, is usually capable of being brought to the big screen. Therefore, it is not surprising that we have seen numerous actors sporting the pointed mustache of the Belgian detective. Adapting a Christie novel is often synonymous with box office success, but in reality, it is a double-edged sword that can only turn out very well or turn out to be a complete failure.

Why would a movie version of such a well-known and beloved character fail? Precisely because of his fame, because of his uniqueness and because of the ease we have to recognize the character. If the Poirot we see on the screen differs too much from the one in the books, the feeling will be one of deep rejection. This is what happened to poor Kenneth Branagh in 2017 with his Murder on the Orient Express and that is, if you have not read the book, the movie may have its charm, but if you know the character, Branagh’s detective will seem like everything but Hercule Poirot.

A lot of action, a lot of licenses and, above all, a Poirot that is too agile, too thin and not very credible. Poirot would never have resorted to violence, never would have been involved in situations with too much action. He is a methodical, calm and leisurely character, like the Christie novels. Likewise, the events narrated in Murder on the Orient Express take place in a confined, claustrophobic space, with little action and a lot of dialogue.

The key to Christie’s work is to discover in a progressive and deductive way, to move through small, well decorated and luxurious spaces … Something that, perhaps, does not fit too much in the mass cinema of the 21st century and, for this reason, the Branagh’s version does not finish curdling. At the same time, the shadow of another adaptation weighed on the memory of many, the 1974 version in which Albert Finney played a great Poirot (albeit with a certain stiff neck).

Perhaps, the passage of time has not played a good pass on this detective ; For this reason, we are left with the classic interpretations of Peter Ustinov and, of course, with the masterful one by David Suchet who, for years, has given life to Poirot on television. It is not bad to reinvent a work, but in the face of such unique characters, it may not be a great success. Sometimes it is better to keep a good memory than to try to fill an already well-lit place with lights.

Christie always wanted to end the character that catapulted her to success, with the unbearable and lovable Hercule Poirot, therefore, Telón wrote , to “assassinate” the character. The writer kept the work in a drawer for years until, when the time came, Hercule Poirot’s gray cells had to rest forever. Such was the character’s popularity and the impact of his death that The New York Times published the only obituary that has been dedicated to the passing of a character.