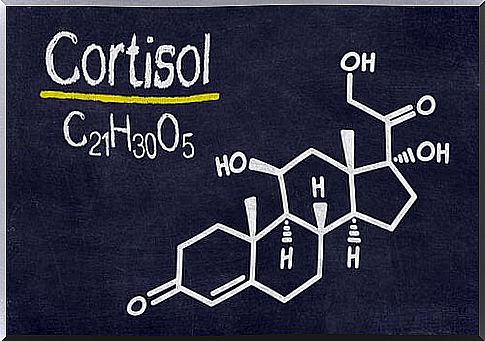

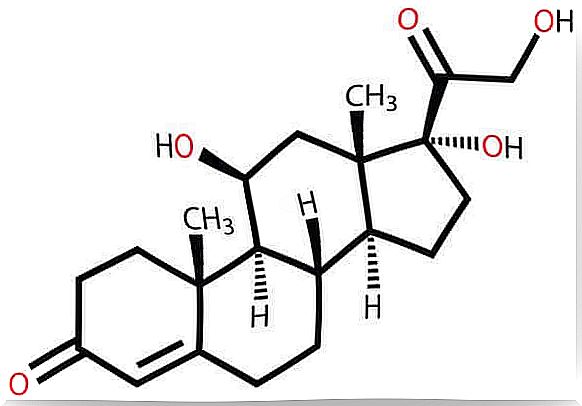

Cortisol, The Stress Hormone

Cortisol is a hormone that acts as a neurotransmitter in our brain. Considered by the scientific community as the stress hormone, our body produces it in stressful situations to help us deal with them. The release of this hormone is controlled by the hypothalamus, in response to stressful situations and a low level of glucocorticoids in the blood.

Stress is an emotion / emotional state that generates physical tension. It can come from any situation or thought that makes us feel frustrated, angry, or nervous. In small doses, stress can be positive, such as when it helps us avoid danger or fulfill our purposes. However, when stress goes from being a one-time emotion to a recurring emotion or emotional state, it can damage our health.

Through the way we think, believe, and feel we can condition our cortisol levels. Scientific evidence shows that by modifying our thoughts in a certain way we are modifying the biochemical activity of our brain cells.

Lack of a sense of humor, being constantly irritated, or having persistent feelings of anger are possible indicators of elevated cortisol levels. Like the permanent presence of fatigue without having made an effort to justify it and the lack of appetite or excessive gluttony. Depending on our character and how we take life, we will generate cortisol or serotonin.

What is cortisol?

Cortisol is a glucocorticoid. It is produced in a very specific area of our body called the adrenal cortex, located just above the kidneys. Its production is regulated by two basic elements: adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and our circadian rhythms. In turn, and no less important, the regulation of these two processes depends directly on the pituitary, a small gland located in the hypothalamus.

Cortisol, the stress hormone, insomnia and key in our daily activation

Situations that we interpret as stressful increase our cortisol levels. However, this glucocorticoid, despite how badly we have painted it, is essential to have a good quality of life. The reason? A medium and balanced basal level of cortisol in our body helps us to stay awake and active during the day, and it is reduced during the night to facilitate rest.

- In fact, Harvard Medical University conducted a study with several hospitals where it showed that a moderate level of cortisol is key to human well-being. It is not, therefore, a matter of reducing its presence to the maximum, since our brain needs that average activation to function much better in our day to day life.

- Now, it must be said that cortisol levels are also variable within the day itself. There are people who are more active in the morning and others who do not pick up a rhythm easily even after eating. However, the normal thing is that it gradually decreases as the day goes by, reaching minimum levels when it is time to fall asleep.

However, if cortisol levels do not decrease at night, due to the stress response being active, it is normal for us to find it difficult to fall asleep. Cortisol plays an important role in our health and well-being, raising its levels with each problem that we identify as a threat.

- When our cortisol levels are optimal, we feel mentally strong, clear, and motivated. If, on the other hand, they are short, we tend to feel confused, listless and fatigued.

- Regulating stress is important and in many cases it is not easy. In a healthy body, the stress response appears and then allows the relaxation response to take over. If our stress response is activated too often, it is more difficult to turn off and therefore imbalance is more likely.

On the other hand, when stress remains, and the desired relaxation does not come, we get sick.

Cortisol and our cognitive performance

This fact is important as well as interesting: a high and chronic level of cortisol will directly affect our cognitive processes. That is, skills such as memory, attention, problem solving or even decision-making can be affected if the level of this hormone is excessive.

Furthermore, studies such as the one carried out at the University of Rochester and the University of Minnesota and El Monte and published in the journal Child Development reveal that those children raised in stressful and dysfunctional environments show poor cognitive development. Elevated cortisol affects brain development, which is why they can present serious problems in learning and in school performance.

Stress produces many diseases

Stress is the way the body tries to solve a problem, but when the situation becomes recurrent, it can cause diseases such as diabetes, depression, insulin resistance, hypertension and other autoimmune diseases. Our body’s response to stress is protective and adaptive in nature. On the contrary , the response to chronic stress produces a biochemical imbalance that, in turn, weakens our immune system against certain viruses or disorders.

Research has shown that recurrent or very intense stress is one of the factors that contribute to the development of somatizations, as a consequence of the lack of adaptive capacity to changes. There are many psychosomatic illnesses produced by stress or triggered or aggravated by it.

When acute stress is continuous, our body can produce ulcers in different parts of our digestive system, as well as cardiovascular problems. Even in people with high risk factors it can cause heart attacks or strokes. All these diseases tend to progress silently, somatized in different ways and in different areas of the body according to certain characteristics of the affected person.

Social support lowers cortisol levels

A biological psychology study at the University of Freiburg in Germany, led by Markus Heinrichs, showed for the first time that, in humans, the hormone oxytocin plays a key role in both stress control and stress-reducing effect. Oxytocin is also that essential element that regulates and favors social behavior (stress modulating factor).

It is difficult to control our blood cortisol level, we know, but there are certain factors that are easier to regulate directly and that can help us. We are talking about having a good social support network (people you feel you can count on and can really count on) or reducing the consumption of certain substances, such as alcohol or tobacco, which indirectly increase our cortisol levels.

A more varied and balanced nutritional diet also helps to regulate the levels of this hormone, since a decrease in caloric intake can increase cortisol levels. In addition, including relaxation and meditation exercises in our routine reduces the risk of experiencing chronic stress, a study from Ohio State University has concluded.

According to this study, the simple difference between those who meditate and those who don’t is immense. Let us therefore not hesitate to take that simple step. Our mind needs a space of peace and balance. And when she is calm, her own body and the whole world tune into that same point of magical well-being. It’s worth a try.

Bibliography:

Aguilar Cordero, MJ, Sánchez López, AM, Mur Villar, N., García García, I., López, R., Ortegón Piñero, A., & Cortés Castell, E. (2014). Salivary cortisol as an indicator of physiological stress in children and adults: systematic review. Hospital Nutrition , 29 (5), 960-968.

De La Banda, GG, Ángeles Martínez-Abascal, M., Riesco, M., & Pérez, G. (2004). The cortisol response to a test and its relationship with other stressful events and with some personality characteristics. Psicothema , 16 (2), 294-298.

Dickerson, SS, and Kemeny, ME (2004). Acute stress factors and cortisol responses: a theoretical integration and synthesis from laboratory research. Psychological Bulletin , 130 (3), 355.

Heinrichs, M., Baumgartner, T., Kirschbaum, C., and Ehlert, U. (2003). Biological Psychiatry , 54 (12), 1389-1398.

Romero, CEC Stress and cortisol.

S Moscoso, M. (2009). From the mind to the cell: Impact of stress on psychoneuroimmunoendocrinology. Liberabit , 15 (2), 143-152.

Valdés, M., & De Flores, T. (1985). Psychobiology of stress. Barcelona: Martínez Roca .